The Duke Ellington Orchestra

A Century of Swing

by Ken Steiner, Duke Ellington Historian

photo by William Gottlieb

Duke Ellington’s duo roles as bandleader and composer were inseparable.

He led a band for half a century, in part, he explained, so he could immediately hear his latest compositions. “My reward is I get to hear the orchestra,” offered Duke when denied the Pulitzer Prize in 1966. Duke chose musicians with distinctive sounds and personalities and famously said that he couldn’t write for someone until he knew how they played poker.

And, of course, the band members contributed their ideas in return; indeed, the orchestra created Duke Ellington’s music.

Ultimately, Duke made the Orchestra what it was. From his piano, Duke drove the band musically, like the way he drove them to tour relentlessly and work 300 or more days per year. Duke conducted and cued the band, introduced tunes with stirring intros, and inspired soloists with his percussive playing.

Duke Ellington plays the piano, but his real instrument is his band.”

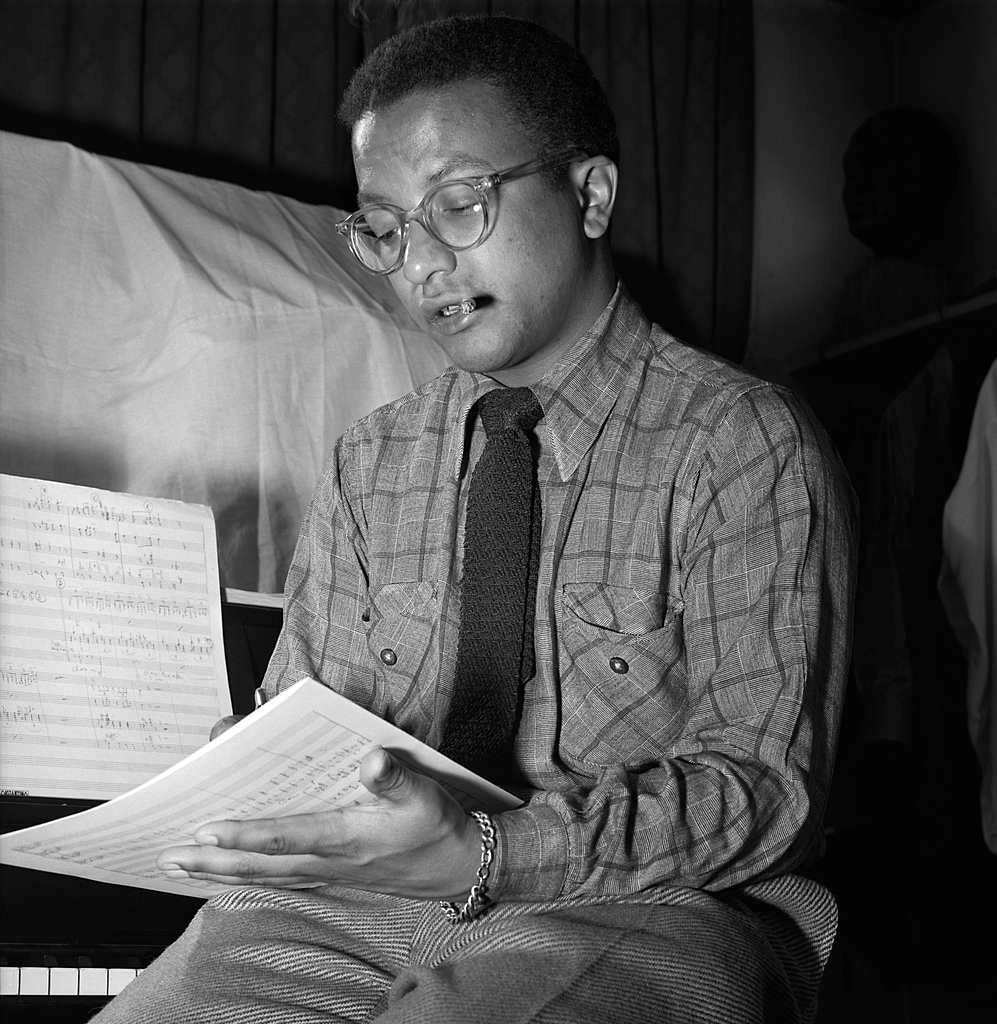

Billy Strayhorn

The Duke across the decades

Duke in D.C.

In Washington, D.C., Duke Ellington began leading small bands while still in his teens. In 1919, he placed an ad in the phone book for “Duke’s Serenaders.” The band, of about five pieces, played in both Virginia country clubs and Washington dance halls. The charismatic Duke attracted other musicians to his side. Sonny Greer, “the sweet-singing drummer” with an out-sized personality met Duke in 1920.

In 1923, Greer and Ellington left Washington to try New York City, along with two of Ellington’s high school friends, saxophonist Otto Hardwick, and trumpeter Arthur Whetsel.

Duke on the rise

The Washingtonians, a six-piece band under the leadership of banjoist Elmer Snowden, opened at the Hollywood Café on September 1, 1923. The cellar club near Times Square had a stage so small that the piano sat on the dancefloor. Trumpeter Whetsel would soon leave to return to school in D.C.

The Washingtonians recruited Bubber Miley who brought a low-down, “dirty” sound to the band. The music changed. As Duke recalled, “That’s when we decided to forget all about that sweet music.”

By February 1924, Snowden was deposed as leader and left the band. Ellington was elected leader, a post he held for the next 50 years. Fred Guy took over on banjo (he switched to guitar in the 1930s). The Hollywood, closed twice by fires and the target of a Prohibition agent’s raid, re-opened as the Club Kentucky in 1925. Trombonist Joe “Tricky Sam” Nanton was recruited in 1926; baritone saxophonist Harry Carney in 1927.

The lower-registered instruments became important parts of Duke’s sound palette. He expanded his band to as many as ten pieces for theatre engagements and tours of New England dance halls.

Duke opened at the Cotton Club on December 4, 1927, with an orchestra of twelve pieces: Duke on piano; two trumpets, a trombone, three reeds, a violin, and three in the rhythm section. Although the Harlem Club was strictly segregated, Duke and his “Cotton Club Orchestra” gained national fame through radio, recordings, and movies.

Ellington added more important pieces: Johnny Hodges (alto sax), known for his creamy sound on ballads, but equally adept at up-tempo blues; Charles “Cootie” Williams (trumpet), who replaced Miley; Juan Tizol (valve trombone) from Puerto Rico; Barney Bigard (clarinet) and Wellman Braud (bass), who brought the flavor of New Orleans, the birthplace of jazz.

Duke on the road, in the Depression, and through the Swing Era

The band left its Cotton Club home in 1931, crisscrossing the United States during the Depression years,. They worked and traveled incessantly: week-long theatre stands with four or more shows per day, as well as dances and nightclub engagements.

The orchestra expanded to fourteen members in 1932 with the addition of Lawrence Brown (trombone) and the return of Otto Hardwick. Ivie Anderson became the band’s vocalist. Her recording debut, It Don’t Mean a Thing (If it Ain’t Got That Swing) heralded a new era in popular music. The band’s personnel would remain remarkably stable during the Swing Era.

Rex Stewart was a notable addition in 1934. He created unique sound effects on his cornet and wrote the books Jazz Masters of the Thirties and Boy Meets Horn.

Billy Strayhorn was introduced to Duke backstage between sets and at the Stanley Theater in Pittsburgh in November of 1938, where the younger man demonstrated his compositions and arrangements of Ellington tunes. “I’ve got to get you in my organization” Duke reportedly said. Strayhorn joined the Duke Ellington organization in February of 1939, his position undefined.

Although usually listed as “arranger,” Strayhorn’s contributions are impossible to overstate. Duke said that he “was my right arm, my left arm, all the eyes in the back of my head, my brain waves in his head, and his in mine.” Although contemporary reports described him as “Ellington’s alter-ego,” Strayhorn was a distinct and brilliant composer in his own right. Strayhorn was also a superb pianist and often substituted for Duke in performances and rehearsals.

Duke discovered Jimmie Blanton, the “Father of Modern Bass,” in St. Louis. Tragically, Blanton died of tuberculosis in 1942.

Duke in the War Years and post-war challenges

Ben Webster joined as the band’s first full-time tenor saxophonist, ushering in the “Blanton-Webster Band” era. The band reached a pinnacle of creativity, recording an abundance of three-minute masterpieces in the years 1940-42. World War II affected the band’s stability, with several changes. Jazz was becoming concert music; Duke made his Carnegie Hall debut on January 23, 1943, where he premiered his 47-minute “tone parallel to the history of the Negro in America” titled Black, Brown, and Beige. Important new members included bass virtuoso Oscar Pettiford, and clarinetists Jimmy Hamilton and Russell Procope. American society changed after the war. Dance halls were closing, and the Big Band Era ended with them. Duke persevered.

Duke’s rebirth at Newport

Duke faced increasing challenges in keeping his orchestra together. Jazz was dominated by small groups playing bebop. Rock’n’roll was emerging. Young Black people gravitated to rhythm & blues. Television and the baby boom were keeping people at home. The band that once traveled in private train cars was now riding on drafty buses. In 1951, Duke was hit with the defection of Johnny Hodges, Lawrence Brown, and Sonny Greer.

For a time, Billy Strayhorn discontinued his relationship with both the band and the bandleader himself. Duke recruited the dynamic drummer Louie Bellson, tenor star Paul Gonsalves, and trumpeter Clark Terry. Duke experienced a rebirth of popularity at the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival when a ten-minute Paul Gonsalves solo drove the crowd into a frenzy. Duke later joked, “I was born at Newport.”

Duke as International Ambassador of Goodwill

Duke Ellington and His Orchestra travelled extensively abroad in this decade, and on occasion, on behalf of the U.S. State Department. Duke wrote suites that reflected the bands’ travels and produced his first two Sacred Concerts. Cootie Williams returned to the band in 1962; Ben Webster also returned on an intermittent basis. Duke resisted suggestions that he focus on composing and disband his Orchestra; he could not compose without it. They suffered two painful losses: Billy Strayhorn died in 1967, and Johnny Hodges in 1970.

Duke as composer to the end

Although ill with cancer, Duke continued to tour relentlessly and write new music. He presented the Third Sacred Concert in 1973 and was working on an opera, Queenie Pie, at the time of his death on May 25, 1974.

The band continued under the leadership of Duke’s son, Mercer Ellington until Mercer died in 1996. Mercer had devoted his life to assisting the band and preserving the band’s legacy. The tradition continues today under the directorship of Mercer’s youngest son, Paul Ellington, the Executive Director of the Duke Ellington Orchestra.