The Music of Duke Ellington

“A New Reason for Living”

by Meg Tripp, writer, editor, and jazz aficionado

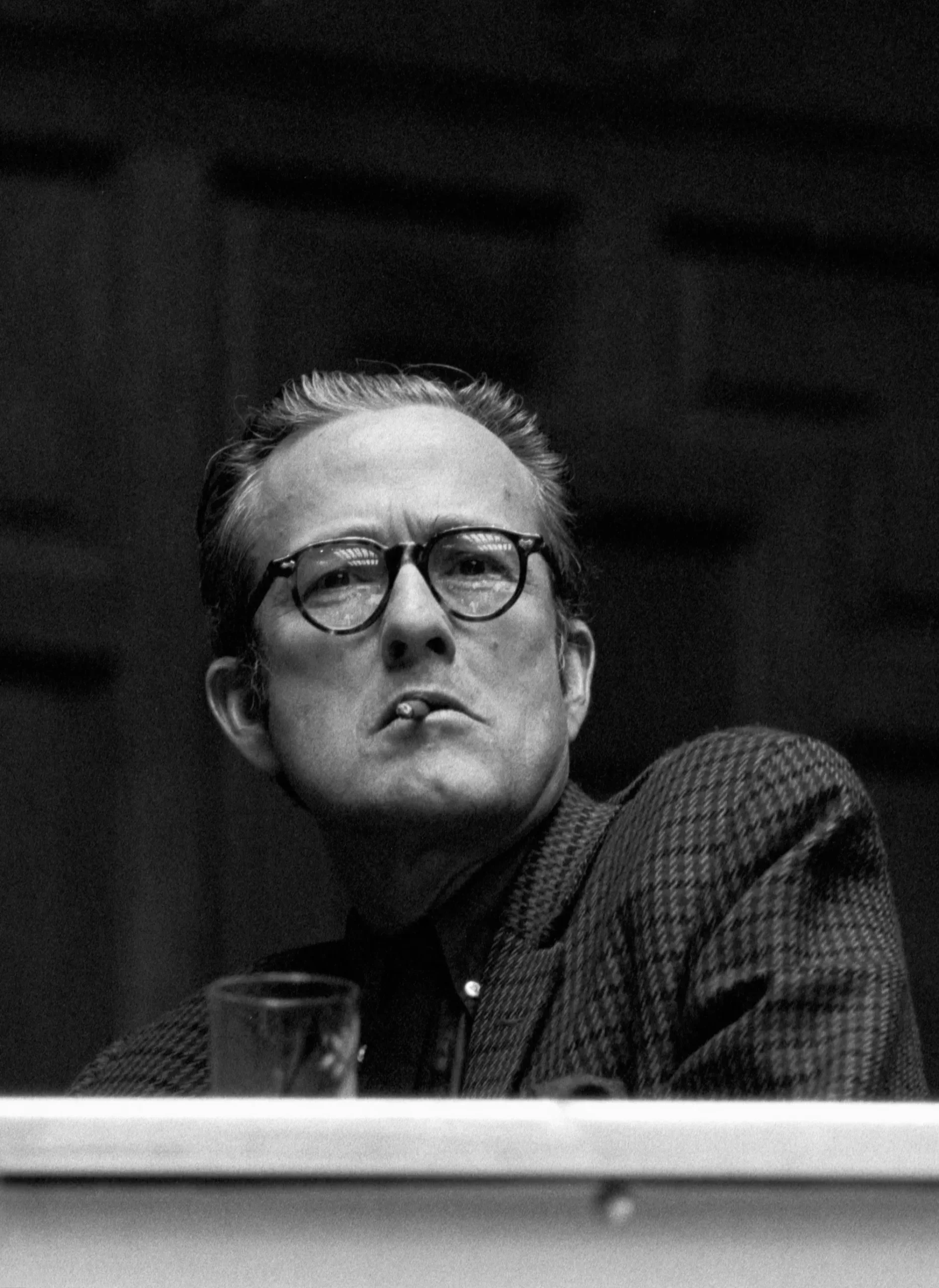

photo by William Gottlieb

While Duke Ellington is perhaps best known for his work as a jazz pianist, composer, and arranger, his work eludes the boundaries of any one genre or label.

He revolutionized jazz itself by mingling the tropes of blues, swing, and big band into his compositions—works characterized by sophisticated arrangements and complex harmonic structures. He was a master of orchestration and combined the different timbres of his band’s instruments to create a unique sound that was instantly recognizable.

Duke’s devotion to his craft and diligence meant no song he crafted was truly done, even decades later. Rather, his performances and recordings captured pieces that were organic, not static. As his orchestra changed players over the years and as new arranging and composing partners entered his life, he was evolving and perfecting what he created.

While Duke was primarily an instrumental composer, the lyrics added to his music have resulted in some of the most frequently sung and recorded songs in American history. Some of his best-known and most often interpreted songs include:

- Sophisticated Lady (1933, lyric by Mitchell Parish)

- In A Sentimental Mood (1935, lyric by Manny Kurtz)

- Prelude To a Kiss (1938, lyric by Irving Gordon)

- I Let a Song Go Out of My Heart (1938, lyric by Henry Nemo)

- I Got It Bad (And That Ain’t Good) (1941, lyric by Paul Francis Webster)

- Don’t Get Around Much Anymore (1942, lyric by Bob Russell)

- Do Nothin’ Til You Hear from Me (1943, lyric by Bob Russell)

- I Didn’t Know About You (1944, lyric by Bob Russell)

- Satin Doll (1958, written with Billy Strayhorn, lyric by Johnny Mercer)

To this day, Duke’s catalog of compositions and lengthy discography make an indelible contribution to American culture. Alongside his recordings, countless artists—in his time, and to this day—have embraced the opportunity to interpret his work on their terms, making him one of the most frequently performed and recorded composers and arrangers in history.

Transcending genre

Duke asserted that jazz music is the most quintessentially American musical genre—one pioneered by Black artists and performers who experienced the indignity of a still-segregated country after years of enslavement.

As he wrote for British magazine, Rhythm, “The music of my race is something more than the American idiom. It is the result of our transplantation to American soil and was our reaction in the plantation days to the tyranny we endured. What we could not say openly, we expressed in music.”

It is not necessary to equate Ellington with Bach to observe that one can listen to both almost indefinitely.”

Ralph J. Gleason

That was certainly, in part, why Duke labeled his music, “American music”—but he also wanted that art to transcend any sort of boundary, including jazz itself. He explored, collaborated, and published within a multitude of genres: from Broadway musicals to sacred suites, from film scores to librettos, from classical compositions to big band dance-floor magnets.

His ability to make new sounds his own and meet the moment found great utility in the Prohibition Era speakeasies of his early career. He played for crowds who wanted a little bit of everything… and he could deliver it all. “Answering requests,” Duke remembered, “we sang anything and everything—pop songs, jazz songs, dirty songs, torch songs, Jewish songs.”

His exposure on the radio, as brokered by his manager, Irving Mills, made him a popular figure across the country with audiences who had never heard anything like the music Duke made. Big band music—the kind he played at the Cotton Club for white crowds having a night out in Harlem—was going mainstream, and there was no more compelling face for the movement than Duke.

Yet every step of the way, he was boldly—yet relentlessly elegantly—challenging the segregation that would have kept him from sitting in the audience to watch his shows. Black and Tan Fantasy and the 1943 Carnegie Hall-debuted Black, Brown, and Beige were at once beautiful and subversive, as Duke made his stand for Black excellence.

Transcending era

When big band music fell out of favor after World War II and dance halls were shuttered, Duke used his royalties to keep his band afloat until a concert at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1956 reminded the world that Duke was not a one-note composer, arranger, bandleader, or pianist.

After coming on late for his set at the third annual festival, the band played a 27-minute version of Ellington’s composition Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue, which featured a solo by tenor saxophonist Paul Gonsalves that lasted for 27 choruses. The audience was ecstatic, and the recording of the concert became a best-selling album, introducing Duke to a new generation of listeners.

He hadn’t gone anywhere, of course—but he embraced the power of the moment and brought the house down.

Over five decades, from taking rowdy requests in New York night spots to performing as a cultural ambassador for the State Department in his later years, he chased his creativity in myriad directions, with a single constant: if Duke played it, it was always worth hearing.

And besides, as Nat “King” Cole said, “Duke will always be 25 years ahead.”

Transcendent collaborations

One of Duke’s greatest musical accomplishments was his capacity to collaborate—and elevate everyone’s efforts in the process.

He brought out the best in every musician who shared his studio or stage. Duke believed the secret to leading a standout orchestra was not to wield a steel baton, but to showcase the talents of his band members, allowing them to shine through solos and improvisations.

Duke both inspired and mirrored greatness in those around him, whether he was evolving I Don’t Mind or Satin Doll with his frequent composing and arranging partner, Billy Strayhorn, or demanding perfection from his musicians during the yearlong recording odyssey that led to the transcendent, Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Duke Ellington Songbook. As Duke said of one of his favorite vocalists and longtime friend, “With Ella up front,” Duke insisted, “you’ve got to play better than your best.”

As John Coltrane’s career was both on the rise in the early 60s and a target for criticism from jazz purists, Duke’s album with the young saxophonist—1962’s plainly named, Duke Ellington & John Coltrane—captured them at a perfectly inverse 36 and 63 years of age.

Duke’s “sit-in” with Coltrane’s quartet showcased Coltrane’s willingness to experiment and push boundaries, while also capturing the enduring resonance and natural capacity for evolution of his fellow boundary-pusher.

The message? He wasn’t afraid to stand up to his growing legacy, and he was eager to bring the next generation along as they made their mark.

Duke ultimately wrote his music like he lived his life: elegantly, boldly, and unapologetically. And that’s why it still resonates today.

Transcendent sounds

While it’s easy to talk about Duke’s artistry at length, we encourage you to dig into one of the following playlists. As the oft-misattributed idiom goes, “Writing about music is like dancing about architecture.”

Or, as we believe, great music speaks—or swings—for itself.

- Duke Ellington at Apple Music Jazz

- This is Duke Ellington on Spotify

- Written by Duke Ellington on Amazon Music

Even better, take the opportunity to enjoy today’s Duke Ellington Orchestra.